WHAT IS THE EXCHANGE RATE? The exchange rate of the Naira is simply the price of foreign currency. Given that the dominant foreign currency in Nigeria, as it is in many other countries, is the US Dollar, the exchange rate in Nigeria usually refers to the price of the US Dollar. Every other currency’s exchange rate, such as the exchange rate of the British Pounds Sterling, derives from the price of the US Dollar.

WHAT DETERMINES THE EXCHANGE RATE? One of the first principles of secondary school economics is that the price of a commodity is determined by the interplay of demand and supply for that commodity. If the demand for a product, like sugar or garri, increases, the price will rise. Consider, for example, the price of accommodation (that is, rent) in newly minted State Capitals like Asaba or Osogbo in 1991. Once demand for housing increased when Delta or Osun States were created and civil servants had to relocate to these capital cities, the price of housing (rent) increased. It does not matter what anyone could have done, rent rose astronomically in these cities because of rising demand.

Similarly, if the supply of a commodity falls, the price also rises. Imagine for a moment that in a town that used to have 10 (ten) bread bakeries, 9 (nine) suddenly close their shops and only one bakery is left. What would happen to the price of bread the next morning? It will rise because the supply of bread has fallen.

So, in general, just like the price of cows or cars, the price of the US Dollar in Nigeria is determined by the quantity of US Dollars that flow into the country as well as the quantity of US Dollars demanded by Nigerians.

Using this simple principle of demand and supply, let us now look at how the exchange rate (that is, the price of US Dollars) has fared in the last couple of years. The simple truth is that the exchange rate in Nigeria has risen/depreciated because it is suffering from two simultaneous effects: the supply of US Dollars is falling at the same time when the demand of US Dollars is rising.

People always refer to the 1970s and 1980s when the Naira was “stronger” than the US Dollar, or at least, were at par (the same value). But the real question to ask is: what was the demand and supply of US Dollar at that time, and what is it today?

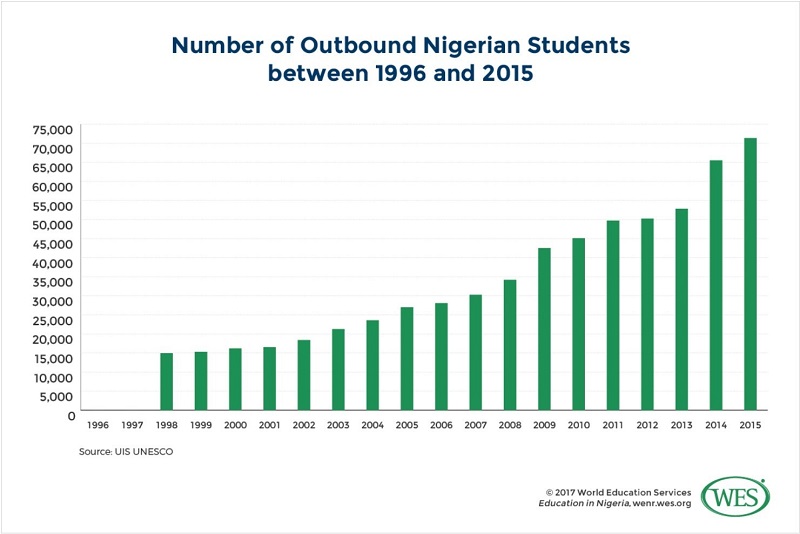

DEMAND SIDE OF THE EXCHANGE RATE: Let us look at the demand first. In the 1980s and 1990s, the number of Nigerians studying abroad (for which US Dollars is needed from here for their upkeep) was negligible. Yet, according to data from the UNESCO’s Institute of Statistics, the number of Nigerian students abroad increased from less than 15,000 in 1998 to over 71,000 in 2015. By 2018, this number had risen to 96,702 students, according to the World Bank.

In the 1980s and 1990s, you would search hard before you can find parents who sent their children to primary and secondary schools abroad. Today, a sizeable amount of the foreign exchange request Nigerian banks receive for school fees are for primary and secondary school education, some of which are for neighbouring African countries. In light of the above, it is no wonder that foreign education has cost the country a whopping sum of US$28.65 billion between 2010 and 2020, according to the CBN’s publicly available Balance of Payments Statistics. If this amount were not sent abroad but was part of the CBN’s Foreign Exchange Reserves, the Naira would be much stronger today.

How about healthcare? No one reading this would deny not ever knowing anyone who has travelled abroad in the last few years specifically to receive medical care. According to the Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA), Nigerians spend over US$1 billion annually on medical treatment abroad. This fact is corroborated by a review of the Central Bank’s balance of payment data, which indicate that Nigerians have spent US$11.01 billion on healthcare-related services over the past 10 years.

Over the last 10 years, therefore, foreign exchange demand specifically for education and healthcare has cost the country almost US$40 billion. As you may know, this amount is equivalent to the total current foreign exchange reserves of the CBN. If we were able to avoid a significant portion of this demand, the Naira would be much stronger today.

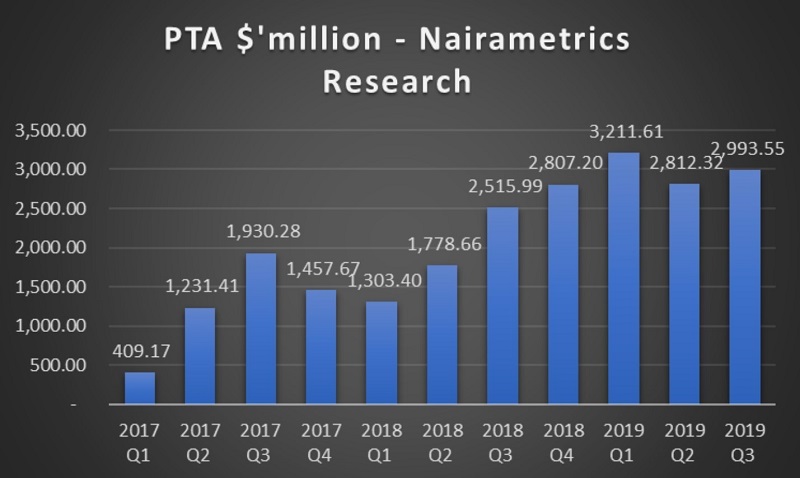

According to Nairametrics, a leading Nigerian online newspaper, Nigeria and its corporates spent a sum of US$55 billion on foreign expatriates for business, professional, and technical services in the last 10 years. Similarly, Personal Travel Allowances gulped a total of US$58.7 billion over the same period. In fact, in the 9-month period between January and September 2019, the CBN sold US$9.01 billion to Nigerians for personal foreign travels.

Still on demand for US Dollars, in 1980, Nigeria’s total imports (for which we need dollars to pay our suppliers) was US$16.65 billion per annum. By 2014, our annual import bill had risen astronomically to US$67.05 billion, though it has gradually fallen to US$54.71 billion as of last year. Similarly, in 1980, food imports cost us US$2.63 billion. We were mostly eating what we produced here in Nigeria. But as of 2011, food imports had skyrocketed to US$18.91 billion, though it has fallen to US$14.84 billion as of 2019.

In 1980, over 75 percent of the cars we drove on our roads were made here by either Volkswagen in Lagos, Peugeot in Kaduna, or some other automobile companies. Today, over 99 percent of the cars we drive are imported (for which we need dollars to make payment). In 1980, most of the clothes we wore were from Nigerian textile mills in Funtua, Asaba, Kano, Lagos, or other numerous towns and cities. Today, almost all the clothes we wear are from imported fabrics.

With this level of demand on education, healthcare, professional services, personal travel, and the likes, the exchange rate will definitely be under constant pressure to rise, particularly when the Central Bank does neither prints US Dollars nor exports Nigeria’s crude oil. Under these circumstances, the price of US Dollars will continue to rise, especially if its supply either remains constant or worse still, falls.

SUPPLY SIDE OF THE EXCHANGE RATE: But that takes me to the supply side of US Dollars in Nigeria. As one of my respected colleagues once remarked, an economy must “earn” US Dollars for the supply to rise. The productive base of the economy must be strong in order to produce goods and/or services that the rest of the world is willing to pay for in US Dollars. In the case of Nigeria, we can do so either by oil exports or non-oil exports.

While we have seen from the analysis above that demand for US Dollars has risen tremendously over the past decades, its supply has unfortunately fallen sharply. Recall that in 1980, our import bill was US$16.65 billion? That same year, we earned US$25.97 billion in exports, leaving us a “savings” of US$9.32 billion. So, in 1980, we were able to meet all the demand for US Dollars from our supply of US Dollars and still had over US$9 billion to spare. In this instance, the exchange rate (the price of the US Dollar) will not rise because, like any commodity, its supply is more than the demand.

By 1996, we earned US$59.83 billion from our exports. That is, approximately US$59.83 billion was “supplied” into the Nigerian economy in 1996. Conversely, our import bill (the demand for US Dollars) for that year was US$25.71 billion, leaving us a surplus supply of over US$34 billion. Indeed, from 2003—2013, we

enjoyed a surplus of US$331.73 billion into the economy. During the same period, oil exports alone accounted for over US$798 billion. Of course, with such “excess” dollars, the exchange rate would be stable, and the Naira would be “strong”.

In the last 12 years unfortunately, oil exports, which accounts for over 90 percent of our foreign exchange supply/earnings, have fallen from US$93.89 billion in 2011 to US$31.4 billion in 2020. This drastic decline, amongst other reasons, implies that the demand for US Dollars has exceeded its supply by about UD$18.45 billion over the last 7 years.

OTHER FACTORS THAT AFFECT THE EXCHANGE RATE: In addition to the fall in crude oil exports, reflecting organized theft, rampant vandalization and exogenous factors, there are many other issues that adversely affect the supply of US Dollars into the economy.

For example, we lose a lot of Foreign Exchange inflows when 80 percent of cargo ships and planes that bring goods to Nigeria (for which we pay dollars) leave our shores empty (implying we do not earn dollars from potential exports of goods they would have carried).

How can we improve non-oil exports (and supply of US Dollars) when the balance sheet (loanable funds) of the Nigerian Export- Import (NEXIM) Bank is less than 10 percent of the balance sheets of comparable countries? For example, the balance sheet of the Export-Import Banks of India, China, South Korea, Indonesia, and Turkey is $18.3 billion, $770.5 billion, $85.4 billion, $6.6 billion, and $25.9 billion respectively. But that of our NEXIM Bank is only $423.4 million. How can we compete in the export market and in the ability to earn US Dollars therefrom with this significant disadvantage in funding?

Over the last several years, thousands of men have relocated their families abroad but continued to work here in Nigeria. Whilst these men are here earning Naira, their major expenses are in dollars for family upkeep, mortgages, car loans, and the likes. This means we have a couple more thousand more people chasing dollars every day, every week, every month. Without going into the reasons for their decisions but imagine that they were reversed and their families were here in Nigeria, the Naira would be significantly strengthened.

Why is it that it takes half the time and half the cost for a container to travel from China to Apapa than it will take for the same container to move from Apapa to Ojota? If it takes 21 days and $8,500 for a 40-foot container to be shipped from China to Apapa, why should it take 42 days and $17,000 for the same container to be moved from Apapa to Ojota? How does this help international trade and inflow of dollars into the economy?

From all of the above, we can deduce that the real problem facing the exchange rate is the simultaneous decline in supply of, and increase in demand for, US Dollars. Holding one constant, any one of them would have been enough to put pressure on the exchange, yet we are suffering from the two at the same time.

It does appear therefore that any objective person would have to conclude that the issue of stabilizing the exchange rate, while an official mandate of the CBN, is a collective responsibility of every Nigerian. And unless and until we stop the scapegoating of one another but rather look introspectively at the issues and honestly work on changing our fortunes, the exchange rate will continue to suffer undue and avoidable pressures.

HOW THE CBN’S POLICIES ARE HELPING TO STABILIZE THE EXCHANGE RATE: So when you hear that the CBN is massively investing in Agriculture to boost local food production, in the power value chain to improve electricity supply, in cotton farming to resuscitate our textile mills, in universities to enhance our educational quality, in manufacturing plants to boost local production, and in health care to curb medical tourism, I hope you now know why.

I hope you now know why the Bank initiated the 41-item policy to curb imports of items we are producing or can produce locally, after all, it has reduced imports from US$67.05 billion in 2014 to US$54.71 billion in 2021. I hope you now know why the CBN established the RT200 FX Program to significantly improve our non-oil export earnings. I hope you now agree with the Naira4Dollar policy that has lifted remittances from an average of US6 million per week in December 2020 to about US$92 million per week as of March 2022.

I hope you can now empathize with the CBN’s situation and understand that the exchange rate’s stability or the Naira strengthening is not rocket-science but requires us as a country to improve our US Dollars earnings capacity and reduce our appetite for importing anything and everything.

Our problems may appear significant, but there are tested and trusted solutions.